The Twists And Turns Of Life On The Edge

Climbers are not crazy people. They are not trying to get themselves killed. They know what life is worth. They are in love with living.

- Walter Bonatti

I am a nomad, not a farmer. I am an adorer of the unfaithful, the changing, the fantastic. . . . Good luck to the farmer! Good luck to the man who owns this place, the man who works it, the faithful, the virtuous! I can love him, I can revere him, I can envy him. But I have wasted half my life trying to live his life. I wanted to be something that I was not. I even wanted to be a poet and a middle class person at the same time. I wanted to be an artist and a man of fantasy, but I also wanted to be a good man, a man at home. It all went on for a long time, till I knew that a man cannot be both and have both, that I am a nomad and not a farmer, a man who searches and not a man who keeps. A long time I castigated myself before god and laws which were only idols for me. That was what I did wrong, my anguish, my complicity in the world’s pain. I increased the world’s guilt and anguish, by doing violence to myself, by not daring to walk toward my own salvation. The way to salvation leads neither to the left nor the right: it leads into your own heart, and there alone is God, and there alone is peace.

- Herman Hesse, Wandering

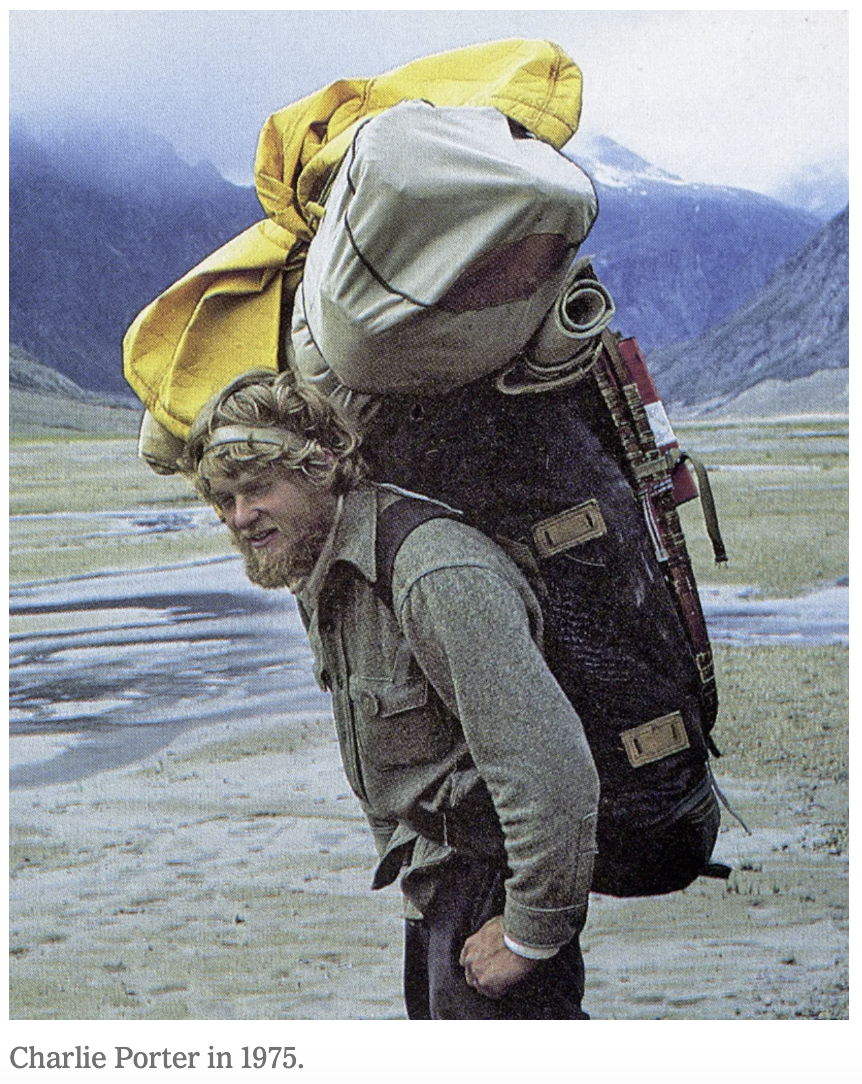

Yesterday, a writer working on an article about legendary climber Charlie Porter contacted me about an interview I did of Charlie in the early 1990s. The process of looking up and reviewing my notes led me back to the following thoughts about an experience I had when I was sixteen. It has been on my mind a lot lately. If anyone ever lived a huge life on the edges of the human enclosure it was Charlie. (More here).

. . .

When you live in the safe and narrow, and things turn terribly wrong, you need to scurry back to the comfortable, and hope for the best. When you live on the edge, try to suck the marrow out of life, experience life in a deep way, you need to expect that from time to time, things will spin out of control. You have to expect an occasional rapid a little too extreme for your skill level. You have to expect that your rope or a knot will occasionally fail on a sheer rock face. There will be times on the vast oceans where your little sailboat will struggle in the whitecaps. If you don’t expect that from the outset, and have a fallback plan, sooner or later that life will get you. Get you absorbed back into the Great Mystery.

I don’t know much about life in the straight and narrow. I don’t know what it takes to succeed at that life, assuming success is possible or even desired. I’ve learned a multitude of lessons about living on the edge. Here are the major ones in addition to the one mentioned above – always have a fallback plan:

On the edge, life gets exhausting. You need a downtime plan, a time built into your routine to relax, sleep, think, meditate. You need solo time. Time to let your mind meander and exist in a no stress, low-risk paradigm before you embark on your next adventure. Without recuperation, you start making bad decisions.

On the edge, you need to travel with a minimum of baggage. The more stuff you accumulate, and try to protect, the slower you move. And life on the edge tends to rub the rough edges off your stuff. It tends to erode bank accounts. There’s a lot of friction, a lot of gravity to fight, in life on the edge.

On the edge, you travel fastest alone. It is more fun with a close friend, and there is definitely a place for travels with someone you love, someone you care deeply about, but in a group of more than one you travel at the speed of your slowest companion. So it is a tradeoff –- joy versus expediency. You need to know who you are and what you want out of life. That’s true, I assume, in the safe and narrow too, but on the edge, if you don’t know who you are and what you want the consequences, the risks, expand exponentially.

So much in life, in the success of a human life, depends on knowing who you are and what you want. That crucial clarity is so difficult to achieve. I think often now, at the age of sixty-seven, of three pivotal weeks of my life when I was sixteen. I spent them alone in a tower in Canada’s subarctic looking for forest fires. Ultimately, the loneliness became profound. I left that tower not knowing who I was. That led to decades of unnecessary twists and turns. Or maybe they were necessary, for instance to the creation of Heron Dance, to make it what it is. I don’t yet know.

Before those three weeks, I envisioned a life for myself in nature, in wilderness. I envisioned a quiet, introspective life involved, in some way, with the arts. I envisioned a life in close connection with my quiet interior. After those three weeks, I envisioned a life of business, a life in the city, a life of women and financial success.

Who am I? What do I want out of this precious gift of life? Clarity. That elusive clarity. Quiet time, time in nature, time journaling grappling with that issue –- grappling with yourself -- where do I find peace, where do I find deep joy, what makes my heart sing, where do I find that spring of ambrosia –- is an absolutely crucial exercise on the journey where deep joy hangs out, where a deep experience of life beckons but where the risks are severe and must be carefully weighed.

This evening I came across three photos of Charlie Porter as a young climber, and one of another mountaineer.

Note the joy. Finally, here’s a watercolor of me as a younger man.

The new art journal, Nurturing The Song Within, and the related diary / planner should be mailed in about a week.

These are designed to be important tools on your creative journey.

You can order both here.

. . .

Join Heron Dancers for an exploration of subjects related to creative work each Sunday at 7pm Eastern. More here.